Photos, articles and places from "Around Bamford" Rochdale from Victorian times up to the 1970s and the present day.

Wednesday, 23 December 2020

Waugh’s Well, Scout Moor, Near Edenfield, Lancashire

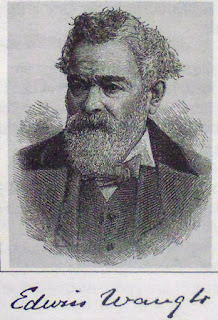

OS Grid Reference: SD 8287 1957. On windswept Scout Moor between Edenfield and

Cowpe in the Rossendale Valley, Lancashire, stands the Victorian memorial known

as Waugh's Well, named after the famous Rochdale-born dialect poet Edwin Waugh

(1817-1890), who was the son of a shoemaker. The poet often came to stay at a

farm on the moors and, very often would visit and sit beside a spring of water,

at Foe Edge. In 1866 a wellhead with a carved stone-head of the poet and a

gritstone wall at either side, was built to honour the man who would come to be

known as the Lancashire Poet Laureate and also Lancashire's very own "Burns".

Following his death at New Brighton the well became a place of pilgrimage for

devotees of the poet, but it was here on the moor at Foe Edge that Edwin Waugh

composed some of his famous dialect poems, all having a strong Lancashire feel

about them. The well lies about ¼ of a mile to the east of Scout Moor High Level

Reservoir on the Rossendale Way footpath. The site is probably best reached from

the A680 road and the footpath going past Edenfield Cricket Club, and then

eastwards onto the moor itself for a few miles towards Cowpe.

Nick Howorth writing in a magazine article (1996) says of Waugh’s Well that:

“The well, originally a spring, was converted into a memorial to Waugh in 1866.

This was an extraordinary tribute to a man who was not only still in mid-career

at the time, but who had only been famous as a writer of Lancashire dialect

songs and poems for 10 years. His fame grew to the extent that by the time he

died in 1890 he was variously called '”The Laureate of Lancashire”' or '”The

Burns of Lancashire”', although he never achieved an international reputation.

The well was rebuilt in 1966 and shows a bronze figurehead of Waugh with his

dates, 1817-1890. His connection with the spring on Scout Moor was that he often

stayed with friends living at Fo Edge Farm near the well, finding the solitude

good for composing songs and poems.

"The name ‘Waugh’ is variously pronounced in Lancashire to rhyme with ‘draw’,

‘laugh’ or cough,…..but today ‘Waw’ is more usual. Edwin was born in 1817 in a

cottage at the foot of Toad Lane, Rochdale, the second son of a prosperous

clog-maker. All was well until his father died of a fever aged 37 when Edwin was

nine years old. Years of penury followed but Edwin’s mother, Mary, held the

family together. She was a devout Methodist, intelligent, and a good singer. By

being careful, she kept Edwin at school until he was 12. She then educated him

at home herself, fostering in him the seeds of artistic talent.”

Howorth goes onto say that: “His early career was a struggle against poverty. He was

apprenticed to a Rochdale printer, Thomas Holden, when aged 14. This gave him

opportunities to read widely although he was often ‘ticked off’ for reading

during the shop hours. He also met local literary figures and politicians. Waugh

held strong Liberal views but his boss was a Tory; they did not get on well.

Between the ages of 20 and 30, Waugh worked in London and the south of England

as a printer, but in 1844 he returned to Rochdale to work at Holden’s. They fell

out over politics and Waugh left in 1847. In that year he abruptly married Mary

Ann Hill, but although he loved her deeply, their natures were so far apart that

the marriage was a disaster.

“For the next five years Waugh worked for the Lancashire Public School Association whose aim was to make a good quality primary education available to poor children. Waugh worked in Manchester, which he hated, but he met many of the city’s literary and intellectual leaders and talked literature, education and politics with other struggling writers. He was beginning to get articles and poems published in Manchester. He worked partime as a journeyman printer, earning money by printing copies of “Tim Bobbin” (John Collier’s masterpiece of 1746). In 1855 he borrowed £120 and published his first volume of essays, “”Sketches of Lancashire Life and Localities””. Then in June 1856 came the big breakthrough when “”Come Whoam to thi Childer an’ Me,”” was published in the Manchester Examiner, bringing him national prominence. The poem was republished as a penny card, earning him £5 for 5,000 cards.

“His reputation was made and he never looked back. His first collection of poems and Lancashire songs followed in 1859. A few of the titles give the flavor: '”God bless these poor folk!”', '”while takin’ a wift o’ my pipe”' and '”Aw’ve worn my bits o’ shoon away.” Apart from courtship and family life, his great love was nature. Many of his essays described excursions far beyond the Lancashire moors, such as Scotland and Ireland. Essays were often published as pamphlets selling for 6d or 1s, eg ‘Over Sands to the Lakes’, ‘Seaside Lakes and Mountains of Cumberland’, ‘Norbreck: A Sketch of the Lancashire Coast’ cost 1d. Waugh’s third area of composition was poetry in standard English. A few titles are: ‘The Moorland Flowers’, ‘Keen Blows the North Wind’, ‘God Bless Thee, Old England’ and ‘The Wanderer’s Hymn’. Subjects like these no doubt reflected the tastes of Victorian England.

Nick Howorth (1996) also adds that: “Another important Waugh activity for many years was giving public readings of his works, rather like his contemporary, Charles Dickens. Although these did not pay very well, they kept his name in the public eye. His big, open, friendly face and soft Lancashire accent made him a popular performer. He did not dress up for these public performances, was always an unkempt figure with big boots, thick tweeds and a heavy walking stick. This emphasized his humble origins to his audiences. In 1869, he read in public almost fortnightly in town halls all over the midlands and the north.

Waugh was an important figure in Lancashire’s literary history because he popularized dialect poetry and made it a valid part of English literature. Before Waugh, Lancashire dialect was difficult to follow, because it contained so many obscure words and spellings. Tim Bobbin, dating from 1746, is the best example of the “”old dialect”’. Readers have to refer constantly to the author’s glossary. Waugh simplified and standardized how Lancashire dialect should be written down, and it has hardly changed since then."

At the western edge of Broadfield Park, Rochdale, overlooking the Esplanade there is a very fine four-sided monument commemorating Edwin Waugh and three other local poets. (See photo below). This monument is called ‘The Lancashire Dialect Writers Memorial’. It was designed by Edward Sykes and erected on the land above the Esplanade in 1900. The pedestal is made of red granite and is topped by an obelisk. The four local poets are: Edwin Waugh (d. 1890), Oliver Ormerod (d. 1879), Margaret Lahee (d. 1895) and John Clegg (d. 1895). This fine memorial is inscribed with various poems and information regarding each writer, with their carved heads. A bit further along the path is a statue of John Bright (1811-1889 the Liberal MP for Manchester. Bright was a reformer and campaigner for the repeal of The Corn Laws (1839). In St Chad’s churchyard, Sparrow Hill, is the grave of Tim Bobbin alias John Collier (1708-1786), the satirical dialect poet who frequented the inns of Rochdale. His grave, with its now worn epitaph, is behind iron railings; but ‘the’ grave has become a place of pilgrimage for devotees of his life and works.

Sources/References:-

Nick Howorth, ‘Edwin Waugh – a man of ink, and his well’, Really Lancashire – A Magazine for the Red Rose County, Landy Publishing, Staining, Blackpool, Issue No. 2, August 1996.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwin_Waugh

http://www.edwinwaughdialectsociety.com/waugh.html

https://thejournalofantiquities.com/2018/03/04/waughs-well-scout-moor-near-edenfield-lancashire/

Copyright © RayS57, 2020.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)